Power in the Palm of Your Hand

In most parts of Asia, smartphones are king. They’re the sole mode of communication for millions of Indonesians, connecting remote island dwellers to the outside world, and the de facto wallet for Chinese consumers. Now, personal devices are also emerging as Southeast Asia’s most potent educational tool — each one a tiny, socially networked classroom capable of supplementing in-school lessons and creating new opportunities for students throughout the region.

These countries are certainly on to something. In the West, out-of-school learning is usually reserved for gifted students or those who are struggling, but personal technology has the power to engage every type of learner outside of the classroom. In fact, at Omidyar Network, we believe that it can be an agent for real change, specifically as a means to narrow the educational gap between wealthy and poor children across rural, urban, and semi-urban environments. The key is to create an ecosystem for what we call equitable EdTech — using technology to empower all learners.

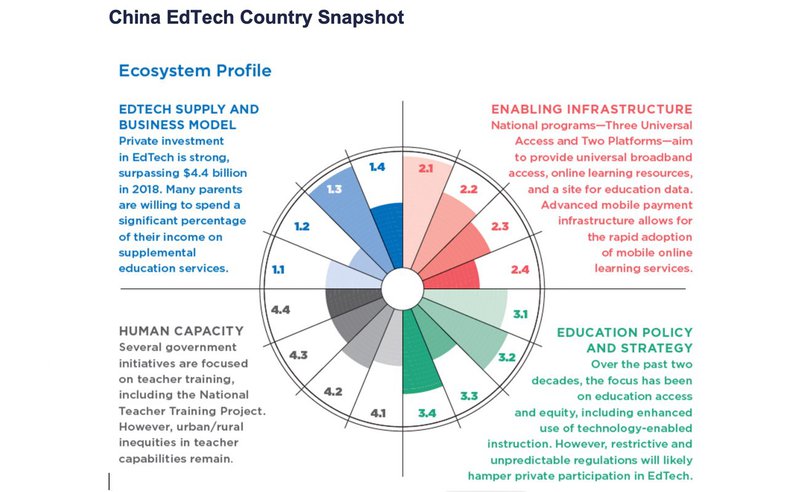

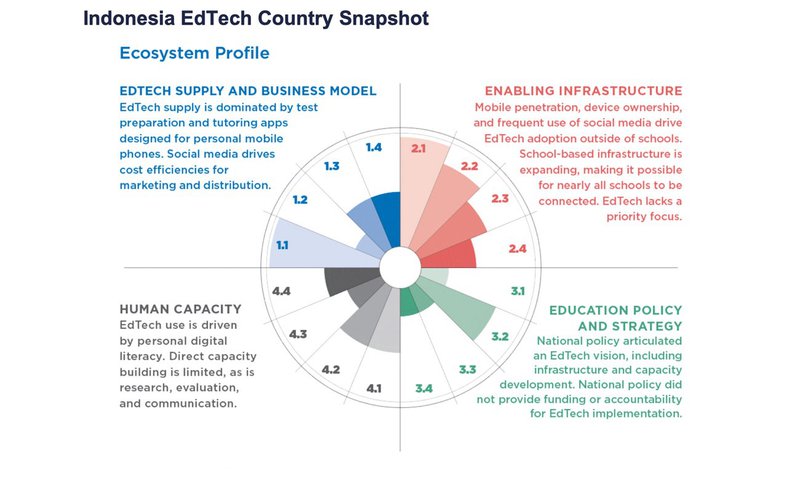

To understand how countries are working to achieve equitable EdTech, this year we published an extensive study entitled “Scaling Access & Impact: Realizing the Power of EdTech.” In partnership with RTI International, we conducted more than 100 interviews with teachers, school principals, education administrators, policymakers, EdTech experts and entrepreneurs in Chile, China, Indonesia and the United States. In these four countries, learners across a broad income spectrum have access to technology for educational purposes.

We discovered that there’s no single prescription for achieving equitable EdTech, nor is EdTech a silver bullet. But when done right, the learning it facilitates can make a big difference in students’ lives. What we uncovered through our model is that equitable EdTech requires four basic elements to thrive at scale: viable business models for EdTech entrepreneurs; an information and communications technology infrastructure backbone to support the distribution and use of EdTech; an EdTech policy backed by legislation and funding; and committed leaders at every level who are dedicated to bringing this vision to life.

We discovered that there’s no single prescription for achieving equitable EdTech, nor is EdTech a silver bullet. But when done right, the learning it facilitates can make a big difference in students’ lives.

Parents Willing to Pay

In China and Indonesia, the present ecosystem is dominated by the consumers. Parents want affordable and convenient ways to enhance their children’s learning, and their willingness to pay for that opportunity has given birth to a thriving, and relatively egalitarian, EdTech industry.

In China, for example, state-administered testing serves as the catalyst for merit-based social and economic mobility. Today, 10 million secondary students take the Gaokao exam, which determines admission into limited-capacity higher education institutions. The average parental spending over the duration of a child’s K — 12 schooling is USD 42,892, much of that goes to China’s USD 50 billion after-school tutoring and test preparation industry.

While in-person tutoring is considered the gold standard, many less affluent parents have gravitated toward online tutoring — particularly since 98 percent of the country’s 802 million internet users have mobile devices. EdTech products available for a one-time fee of USD 10 or less are accessible to most Chinese families. That’s money that rural families can afford without children traveling hours for tutoring and test prep sessions. We found that 27 million students and 2 million teachers subscribe to a learning app called KnowBox Education, a platform that allows teachers to manage and correct homework. One million of those users interact with the service each day. In 2018 China’s online learning market totaled 144 million learners, an estimated 70 percent of whom pay for services.

Expanding Access to Education

Accessibility is a major selling point in China, but in Indonesia, demand is fueled by the constrictions of geography as well. In a country comprised of 17,508 islands, locating a nearby tutor is not always an option. Neither is downloading data-heavy online content, given that many do not have access to high-speed internet connections. To address this hurdle, EdTech companies like Zenius, which offers 81,500 learning videos via DVDs (as well as on its website), and SolveEducation!, provide apps that are easily accessible to smartphone owners. Parents love these innovative workarounds. In fact, spending on mobile learning apps in Indonesia is expected to hit USD 7.7 billion this year.

Teachers have also played a vital role in helping entrepreneurs and nonprofits expand access, particularly in China. Free commercial technologies in China, such as OnionMath, Knowbox, and Zuoyebang that help teachers manage their time with assigning and grading homework and assessing students have grown increasingly popular. As teachers integrate more EdTech into their lesson plans, their students grow accustomed to using these apps. And if an app is being used in school, a basic version may be available to students for free. OnionMath, for example, provides teachers with training and then offers half of its content for free to mobile app users. As a result, more than half of its 20 million customers come from less privileged regions.

The Green Pepper Project, the product of a public/private partnership in China, creates a community where urban and rural teachers can team up. The platform livestreams instruction from teachers in top-tier Chinese schools to many different classrooms. Teachers can either use the technology as a supplement to their own teaching or hand over certain lessons to their live-streamed counterparts. Green Pepper is used by 34,071 teachers in nearly 4,500 schools.

And China and Indonesia are not the only countries in Asia that have taken advantage. Omidyar Network has witnessed something similar in India. Investee Vedantu is an online live teaching platform where hand-picked teachers teach students in cohorts of 250 to 500 while keeping the session highly interactive. The platform also provides 24/7 post-class doubt resolution support, recorded content and an academic mentor for personalized mentorship. The platform attracts 8 million active unique students on a monthly basis.

Governments Help Out

Market demand alone cannot create ecosystems for equitable EdTech. Indonesia and China’s governments have begun to contribute to the infrastructure — technological and political — to continue expanding access. Using technology to distribute content to remote places has been part of Indonesia’s national policy and culture since the 1970s, when the country created Pustekkom, a which is now a central EdTech authority.

In China, teachers cannot obtain their certificates without completing a China Education Technology Standards (CETS) course, which provides core tech skills, like online search, content evaluation, and data security.

Both countries, however, have yet to leverage EdTech to improve quality of classroom education, to the extent that we have seen in countries like Chile and the United States, for example (To learn more about comparisons between Chile and the US, click here.)

Stronger teachers in China still tend to gravitate to the cities, where salaries are higher. And though EdTech — particularly streaming videos and AI-based teaching tools — is helping to smooth out those differences, very few rural schools have the connectivity to close the gap. Only 26 percent of rural schools in China have internet, compared to 77 percent of urban schools.

Indonesia’s national government is beginning to articulate a vision for how it wants EdTech to work within its school system; a clear next step is to allocate the funding and design the legislation to bring that vision to life. For instance, the need for Wi-Fi is so profound that one initiative, Wokbolics, uses cooking woks and USB Wi-Fi pen drives to enable a wireless access range of up to 3 km. In the meantime, the country has yet to train its teachers in EdTech usage in any meaningful way.

Nevertheless, China and Indonesia have laid the meaningful groundwork for further EdTech development. They have created a culture where everyone — students, parents, teachers, business leaders, and policymakers — believes in the transformative power of technology and is open to testing whatever innovations entrepreneurs have to offer. And, when 1.6 billion people believe in something, anything is possible.

This blog focuses on key insights from the “Scaling Access & Impact: Realizing the Power of EdTech” Country Reports for China and Indonesia. There are five reports in the “Scaling Access & Impact: Realizing the Power of EdTech” series. We will be releasing the global report in Fall, 2019.